Time for more film technique: jittery handheld shots are used to suggest the nervousness. Towards the end of the scene, John Williams’ music starts (with drums) and the cutting becomes faster to increase tension.

And let me throw in some film history too: the entire scene — starting with the pool outside the hotel — was in shot in the famous Spanish-style hotel Roosevelt Hotel on Hollywood Boulevard 7000. The hotel was financed by Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford (business partners of Charlie Chaplin in the defunct film studio United Artists).

The same hotel played a minute role in Spielberg’s World War II comedy “1941”: the Chinese-American model designer Gregory Jein built a miniature Hollywood Boulevard to have Wild Bill Kelso’s fighter plane crash-land on it at night. After his work on “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”, Jein thus got a second Oscar nomination for a Spielberg movie.

In the movie, thanks to some minor camouflage — a temporary exterior sign added to the back entrance —, the Roosevelt Hotel poses as the “Tropicana motel”. There was a real Tropicana motel, mainly a hangout for rockstars, at 8585 Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood, but it got demolished in 1988 and the Ramada Plaza West Hollywood (“Ramada Weho”) has taken its place.

Scene 10 — 48:31

The British artist

David Hockney

created the mural you can see at the

bottom of the pool in the tropical patio.

Artsy page on David Hockney

Marilyn Monroe was a regular guest — she even started her career there as a model with a sun-tan commercial… Or need we mention that the very first Academy Awards, better known as “the Oscars”, took place in the “Blossom” ballroom in 1929, two years after the hotel’s opening?

Frank Abagnale escapes arrest by Carl Hanratty by playing a Secret Service agent, saving his essential MICR printer.

Scene 10 — 50:56

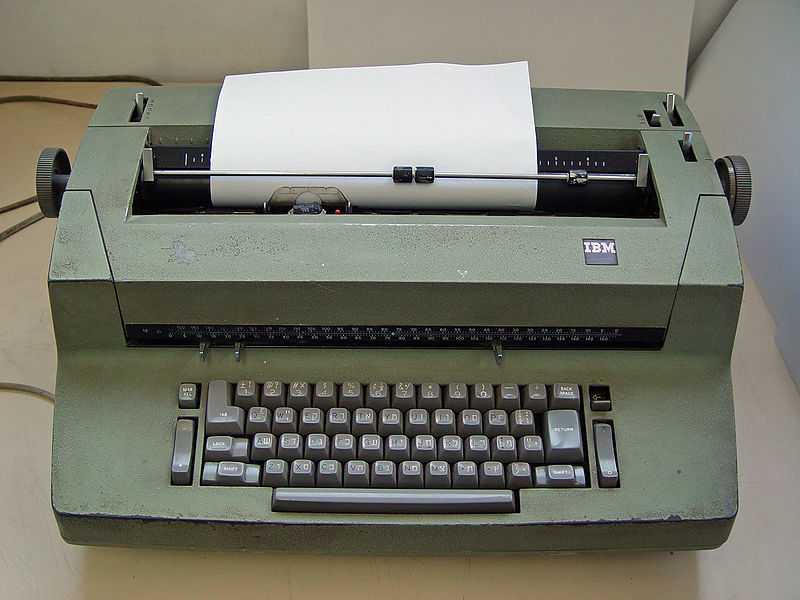

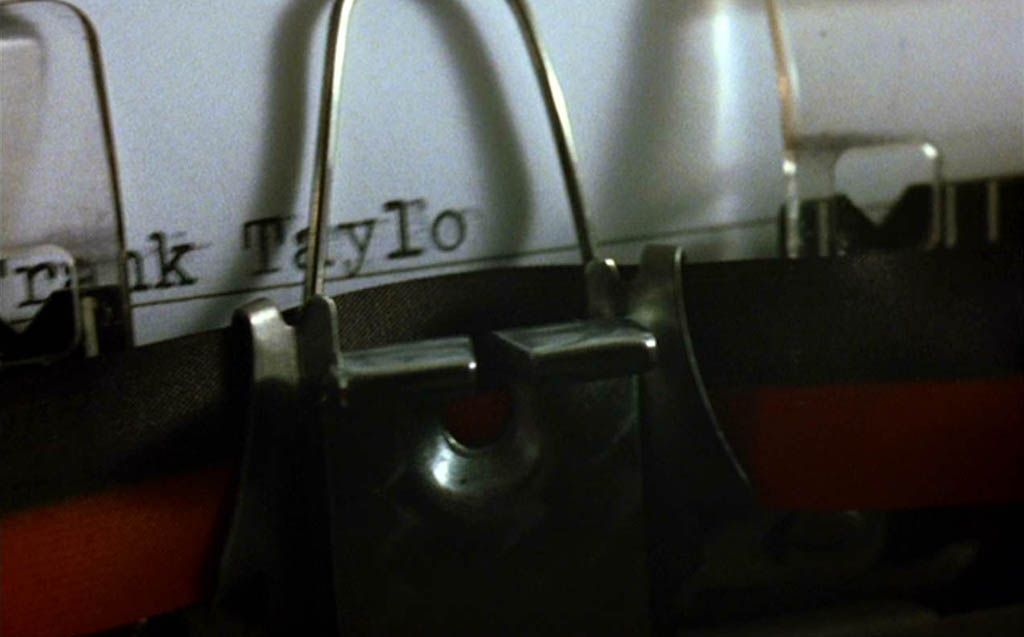

An

I.B.M.

Selectric on the left side,

a MICR

printer on the right side

This “face time” between cat and mouse never happened! Abagnale knew who was chasing him, but didn’t meet Hanratty until after his arrest! (bonus DVD, Cast Me If You Can: The Casting of the Film — Tom Hanks as Carl Hanratty, 1:17-1:21)

Abagnale, one of the greatest imposters and escape artists of all times, never acted as a Secret Service agent but he did act as an F.B.I. agent on several instances!

His book “Catch Me If You Can” details it all:

To distract Hanratty, Abagnale starts to talk about the I.B.M. Selectric.

I.B.M.

Selectric-II electric typewriter

(The same typewriter is also visible in scene 14 (1:22:00): the F.B.I. agents bust into his office at the hospital. The office is empty, but an I.B.M. Selectric was left behind, which tells Hanratty that he’s on the right track...)

After his primitive first trials with the Pan Am pay checks, Abagnale uses the new technology of the I.B.M. Selectric to produce more professional looking checks. “I then rented an I.B.M. electric typewriter with several different typeface spheres [...]. I made a final stop at an art store and purchased a quantity of press-on magnetic-tape numerals and letters.” (book “Catch Me If You Can”, page 92)

(The numerals and letters are magnetic because that makes them adhesive. They get used in the same way as the Pan Am decals were to produce Pan Am pay checks. The forger will not use them to put the routing numbers on the codeline. Doing so would allow the magnetic reading of the check, which goes against “the float”! For the same reason, check forgers won’t use magnetic ink either...)

So, what’s new about this typewriter? It was the first electric typewriter to use a rotating typeball (called “typeface spheres” by Abagnale but often called “golf balls”). The paper is stationary and the typeball moves across it — the opposite of what mechanical typewriters do!

First of all, you get a crisp manuscript with a neat, regular appearance. Unlike the old typewriters, where you hit the typebar directly and thus with unequal force: some keys you hit hard, other less so, and that shows in the typewritten document. And that also means no typos because of clashing typebars. With the electric typewriters — the Selectric-II you see here had a built-in corrective tape — you got a typewritten document that looked printed. This was revolutionary, it was in fact the beginning of desktop publishing (“DTP”) before personal computers even existed!

Scene 7 — 35:19

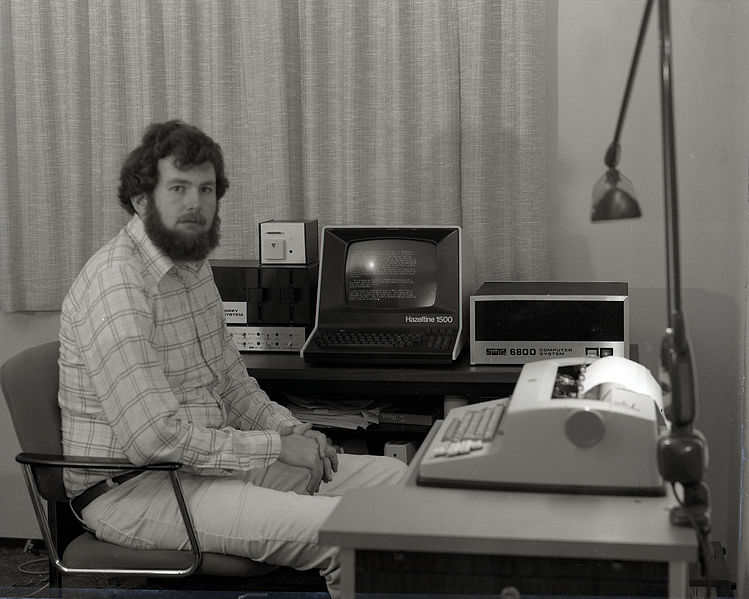

(Actually, these electric typewriters evolved… not into computers but into both printers and computer terminals. Because of their speed and reliability and the absence of clashing typebars, the Selectric typewriters were widely used as terminals for computers, replacing the earlier teletypes.)

Furthermore, the machine had a key lockout feature that smoothed out the irregular fingerstrokes of the typist. When you pressed a key, a narrow metal tab was pushed into a slotted tube full of ball-bearings under the keyboard. These balls were adjusted to have enough horizontal space for only one tab to enter at a time. The typist could press multiple keys at the same time; he knew he would thus cycle the machine in the correct order. This mechanism could process 15 characters per second — not that anybody can type that fast. Users had the impression the machine used a storage buffer, which of course only computers have. This was just mechanical parts with as side-effect the imitation of computer memory.

I.B.M. continued the Selectric product range well into the 80s! The Selectric-III was followed by other models. Some of them were word processors or type-setters rather than simply typewriters. Still, I.B.M. no longer dominated the market by this time: other companies such as Brother, Smith Corona etc. had caught up.

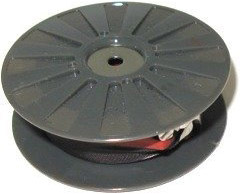

The Selectric-I model used a cloth cartridge or a spool film ribbon! The Selectic-II models with the correction feature had a cartridge film ribbon instead of a spool ribbon, the non-correcting model used the classical cloth cartridge. (Part of) that cloth dries out, so cloth cartridges produce unequal results. Film ribbons put crisp and steady ink on the paper! Call this the start of “printer consumables” if you will…

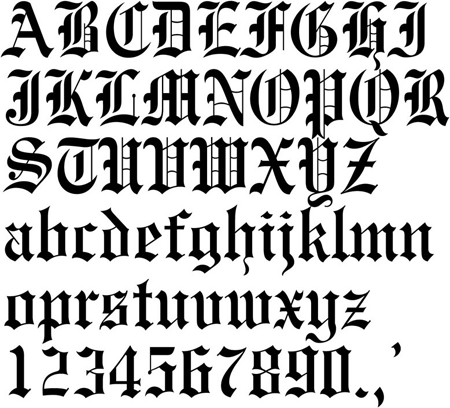

And then there was the ability to change fonts. Here’s an example where the normal style changes into bold and italic text. A few mouse clicks in your wordprocessor is all it takes now, but back then you needed an I.B.M. Selectric and three typeballs to produce this “sophisticated” output! (Looks printed rather than typewritten, doesn’t it? That’s what the equal pressure of the electric machine does when it puts ink on paper!)

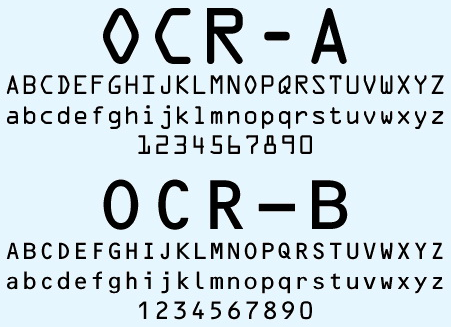

Alongside many fonts, including symbols for science and mathematics, a script font that looks handwritten and the ornate “Gothic” font “Old English”, the typefaces used on checks (OCR-A and OCR-B) quickly became available for banking applications.

Unavoidably, this machine became a dream for check forgers. It was the only way to “print” the OCR fonts on a document without disposing of a printing machine.

And this is directly in the movie! As Abagnale comes out of the bathroom to confront, nay, distract F.B.I. agent Hanratty, he starts musing about the qualities of the I.B.M. Selectric: “That’s the new I.B.M. Selectric — you can change the print type in five seconds. Just pop out the ball.” (scene 10, 50:24)

Unfortunately, the sound engineers did a lousy job here for a few seconds. The text is unintelligible and, frankly, I don’t understand why the sound department didn’t clean this up during the looping (“ADR”). But I listened to the DVD with headphones enough times, and I checked the published screenplay, so you can trust me on this: Leonardo DiCaprio is definitely praising the good old Selectric from 1961 here…